Advertisment

Declining fertility is a huge problem for Denmark

Fertility is now firmly on the public agenda after Mette Frederiksen’s New Year’s speech and current TV and article series.

In today’s Denmark, one in eight children are born through fertility treatment, and this is part of a major societal problem that we are only now beginning to realise.

But why are we having fewer and fewer children? The short answer from Rune Lindahl-Jacobsen, Professor of Epidemiology and Biodemography, is that we don’t know.

– We know several factors that are important, but we don’t know how much each factor matters.

But there’s also a longer, more nuanced answer.

– It is only now that we as a society are realising that low birth rates pose a significant societal problem. And the problem must be seen in connection with the fact that we are living longer and longer.

Fewer children and more elderly people

Globally, far fewer children are being born than just a few years ago. In 1970, the average woman had 5 children. Today, women have 2.3 children on average, and that number is dropping sharply.

In Denmark, the figure is as low as 1.5 children per woman. In countries such as Italy, only 1.2 children are now born per woman. The magic number is 2.1, which is the number of children that must be born per woman to maintain the population size.

– We need to replace our parents. That’s the two children. And then we calculate an extra 0.1 child because some children die before reaching adulthood, Rune Lindahl-Jacobsen explains.

At the same time, we’re living longer and longer. For every year we live, we gain an extra three months or six hours every 24 hours if the trend in life expectancy continues as it has for the last 150 years.

And even though we know that we get less sick at a given age, the number of sick people increases dramatically. This happens because the risk of getting sick increases with age.

This means that the number of elderly people will increase, which will ultimately represent an increased cost for the healthcare system and society as a whole.

– This is why we need hands to create value in society and why we need sustainable fertility.

Young people must support the elderly

After 2050, at current fertility rates, the labour force (15–69-year-olds) will start to decline. And that’s problematic.

For the individual, because he or she may not be able to have the children they want. For society, because there won’t be enough hands to keep society running and support the elderly, a demographic which is going to increase in the coming years.

– National fertility forecasts have been overly optimistic for many years, and significantly fewer children have been born than predicted. We are therefore in dialogue with the forecasters, and they have already lowered their expectations for future fertility rates. That’s pretty significant, he says.

The 7,000 too many children that have been predicted to be born since 2017, but never came, means fewer childcare places, fewer educators, fewer school teachers and fewer education places. And that also means there the labour force will decrease.

If the trend continues as predicted, a situation will arise where there will be too few people contributing income to society compared to those who are costing society money (see figure).

– Importing young people from other countries is of course a solution, but somehow it seems unethical to remove labour when you know that fertility is also declining in middle-income countries, such as China, where the birth rate is 1.28 children per woman, and India, where the birth rate is 2.0 children per woman, just like in low-income countries.

Explanations for declining birth rates

There are many socio-cultural factors that we know can influence our fertility. Education in particular is cited as a factor that has had an impact, as higher education levels of women in a country means lower fertility.

On an individual level, this isn’t necessarily the case. In today’s Denmark, highly educated women have the most children.

– Of course, there are also several other social, economic and cultural factors that influence and can affect women’s behaviour. For example, women can control their fertility using contraception and induced abortion.

According to Rune Lindhardt-Jacobsen, most sociologists and demographers believe that socio-cultural and economic factors explain the fertility rate decline and that the ability to have children (fertility) is constant.

But at the same time, we know that one in six couples globally struggle to have children, as documented in a 2023 WHO report.

– We also know that trends in a number of biological markers of our ability to have children show that our reproduction has deteriorated. Our ability to have children, and therefore our reproductive health, has deteriorated over time.

This is exactly what Rune Lindhardt-Jacobsen and colleagues summarised in an article in Nature Reviews Endocrinology.

Decreasing sperm quality

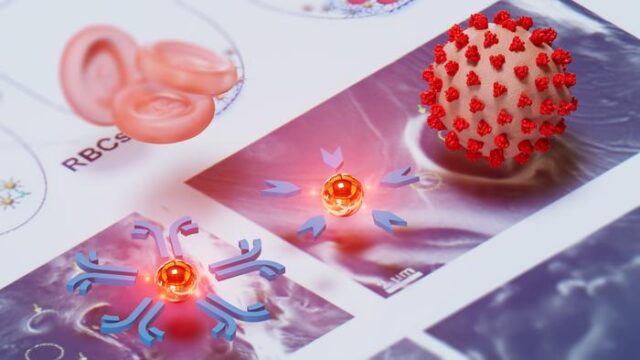

Male sperm quality is decreasing, a trend observed for years in high-income countries. Men’s ability to father children has simply worsened.

A good indicator of this is a study based on semen samples that young men aged 18 were invited to provide when being selected for National Service.

– Here we see that sperm quality is dangerously low. And we’re talking about 18-year-olds who have the best sperm quality they will have in their lifetime.

When comparing sperm quality with historical data from Danish men examined at an infertility clinic in the 1940s, men examined in the 1940s had a sperm concentration of approximately 60 million per millilitre, whereas the young men examined in 2000 only had 45 million per millilitre.

– This is alarming, as 40–50% of young men had sperm concentrations below 40 million per millilitre and will have trouble fathering children.

What affects fertility?

The growing need and demand for fertility treatment speaks volumes about the desire to have children. It is a clear sign that not only social and cultural factors play a role; reproductive health also needs to be considered.

– It is essential to investigate how all the substances we are exposed to in our everyday lives affect fertility. And here, men are easier to examine as it is much more difficult to test women’s fertility, such as determining the quality of a woman’s eggs.

One thing that researchers around the world are focusing on to find the causes of fertility problems is testicular cancer. Testicular cancer is a kind of canary in the coal mine.

In the same way that a dead canary in a coal mine was a sign that there were dangerous substances in the air, the incidence of testicular cancer is a good measure of reproductive problems.

Things go wrong in the foetal stage

Precursors to testicular cancer can be traced all the way back to foetal life. Up until the 12th week of pregnancy, a key process takes place in which the so-called gonads are formed. In women, the gonads become ovaries; in boys, testicles. These are the genitals that produce eggs and sperm, respectively.

If this formation goes wrong due to environmental influences such as endocrine disruptors, it leads to lower sperm quality and precursors to testicular cancer, as well as genital malformations and reduced testosterone levels.

– This means we can trace low sperm quality and precursors to testicular cancer all the way back to the foetal stage. If a woman has been exposed to something environmental, such as endocrine disruptors, it damages the ability of the male foetus to reproduce.

– Therefore, when looking for the causes of low sperm quality, we also consider the incidence of testicular cancer – and on a global level, it’s rising sharply, just as we’re seeing a decline in men’s sperm quality.

A link to fossil fuels

Rune Lindahl-Jacobsen has looked at cases of testicular cancer in men conceived during World War II, and the number is relatively lower than in other periods. There is thus reason to believe that the environmental factors that were different during World War II have an impact on our fertility.

– We observe that fossil fuel use and testicular cancer go hand in hand. The more fuel used, the more cases of cancer.

Fossil fuels are not only used for heating, but also to produce petrochemicals, which is a huge economic market (DKK 4,266 billion annually). Petrochemicals are in everything we surround ourselves with: Clothing, packaging, electronics, cosmetics, furniture and more.

– An example of a little-known fact is that almost everything you buy at the chemist’s is 99% petrochemicals. And we find them in rivers and drinking water around the world.

Petrochemicals are not natural to our bodies and therefore have the potential to reduce our fertility.

– We know this is true for some substances, such as PFAS and phthalates, but there are a myriad of products made using petrochemicals and the ways in which they can affect us, so it’s almost impossible to get an overview of possible effects.

The population must be examined

– As a society, we act on the issue by offering treatment for infertility. It’s great for the individual to get extra help in the form of fertility treatment, now also with free help for a second child, but it doesn’t matter demographically, i.e. on a population level.

Rune Lindahl-Jacobsen believes that there is a need for a national study of Danish fertility so that we can learn more about where to focus our efforts.

– How do we best prevent? How do we get women to start having children earlier? How do we prevent women from being exposed to these environmental impacts that jeopardise the sperm quality of their male children? We need to find out if we want to do something about it.

– The fact is that we know a lot of individual socio-cultural and biological factors that have an impact on fertility, but we don’t know how big their effects are in relation to the others. Therefore, it is difficult to intervene and prevent so that fertility becomes sustainable based on current knowledge.

To find out, Rune Lindhardt-Jacobsen calls for a study to be made of both the socio-cultural (mainly behavioural factors) and the biological (mainly our ability to have children) factors.

– In 1990, the Danish Parliament set up a life expectancy committee, headed by then Minister of Health Ester Larsen, due to the stagnating life expectancy. Similarly, we currently need an interdisciplinary study of Danish fertility if we want to change the low fertility rate. Until that happens, we won’t know how to increase fertility, not only in Denmark but also in other countries.

More info

Rune Lindahl-Jacobsen and colleagues have proposed population studies, in part in a publication published in the European Endocrine Views and by participating in an expert panel in the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. A fact sheet will be published in March to advise the EU Commission.